After my two spectacular nights at the Chateau Lake Louise, it was time to head farther west. It amuses me to think that I had to drive downhill from Lake Louise to the Trans Canada Highway, and then at once begin driving uphill again to reach the summit of the Kicking Horse Pass. The irony is that the summit of the pass is about 100 metres lower than the lake!

But no matter. As you stand at the summit of the Kicking Horse Pass, you are standing on the continental Great Divide. The stream flowing downhill to the east feeds the Bow River, which in turn enters the Saskatchewan River system, and the water eventually winds up flowing into Hudson Bay. On the west, the Kicking Horse River rushes down the mountains, and discharges into the Columbia, which flows into the Pacific Ocean.

Also, as you pass the summit, you cross the border from Alberta into British Columbia -- and you leave Banff National Park and enter Yoho National Park.

It's a further irony that the summit area of the pass looks so neat and benign today, because getting up and down the west side throughout history has been little short of nightmarish for both the original Canadian Pacific Railway and the more recent Trans-Canada Highway.

On the west side, the road swiftly peels downhill along a decidedly steep and twisting gradient which in part follows the original railway right-of-way. The CPR experienced so many derailments on this overly-steep "Big Hill" that they eventually replaced it with the gigantic figure-eight of the two famous Spiral Tunnels. Although there are roadside viewpoints giving somewhat of a view of the tunnels, you really only get the picture when you see a train passing through, with its head end coming out of a tunnel and going over or under the tail end that hasn't gotten into the tunnel yet.

At the bottom of the hill, signs point out the right turn onto the Yoho Valley Road. Note: this road is not passable to vehicles towing trailers. There's a wicked three-leg switchback on the road -- here partly visible behind the trees.

Any vehicle over 7 metres long has to back up (or down) the middle leg of the switchback, since there's no room to turn such a big vehicle around the hairpin bends. I've seen motorhome drivers lose their cool when trying this in the past. If in doubt, take a tour and leave the bus driving to the professionals.

This road has a lot of twists and turns, but climbs steadily and sometimes steeply to the north and into the Yoho Valley. It's a fascinating experience. The road is walled in by towering forests of evergreen trees, and mountain peaks loom into view from time to time over the trees on all sides. The name of the valley and the park comes from the Cree word "Yoho!" -- an expression of awe and wonderment. This place certainly is awe-inspiring.

Eventually you reach the end of the road -- but you're only halfway up the valley. Further progress is on foot only. But here at road's end is the most amazing sight of Yoho, the stunning Takakkaw Falls. This Cree name means "It is magnificent." Yes.

The falls are fed by an icefield and glacier high atop the Great Divide. The river plunges in four steps (the first one is hidden at the top) for a total drop of 373 metres, with the main fall descending 254 metres -- the second tallest waterfall in Canada. In these pictures, notice how the force of the falling water on the second stage is sufficient to make the water rocket upwards into the air before plummeting over the main drop.

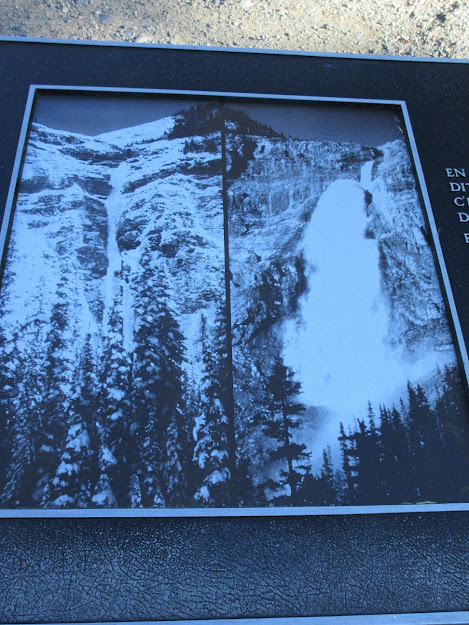

Here, for comparison, is a pair of photos from the display board at the site, showing the falls frozen during the winter, and then the eye-popping torrent of water during the spring snow melt.

Although you can take decent pictures from the car parking lot, you should follow the level paved trail to the right of the parking area for about 8-10 minutes. You'll come to a footbridge across the river, which you can cross to get even more up-close and personal with the falls. Otherwise, climb the sharp little hill right by the bridge and you'll get a grandstand view. The advantage of walking here is that from this viewpoint the sun will be partially behind you, even in early morning. From the parking lot the morning sun will be partially in front and will affect the quality of your pictures (voice of experience, from previous visit).

Back out on the main highway, continue west past the small town and railway mustering yard of Field. A little farther along, turn right on the Emerald Lake Road. This road runs parallel to the highway for a short distance and then bears away to the north, up another valley. At the point where the road turns north, look on the left for the Natural Bridge signs.

This unique formation was originally a waterfall until the roaring waters of the Kicking Horse bored themselves a new channel. In spring runoff time, with all the snowmelt, the river often overtops the barrier and temporarily turns it back into a single waterfall again. Be sure to check it out from all angles, on both banks of the river and from the footbridge.

The road from here north to Emerald Lake runs fairly straight and uphill, but nowhere near as steep a hill as in the Yoho Valley. As you near the road's end, pay attention to the speed limit signs. You're going to roll right into the parking lot with almost no warning. It's not very big, and even in the early morning you may have to drive around it once or twice to find a spot. I got lucky as soon, as I arrived, but by the time I left twenty minutes later, the newcomers were having to park along the exit road some distance to the south.

Emerald Lake is another one of those gorgeous spectacles that looks completely different in every season and every kind of light. The last time I drove in there was a cloudy, foggy day but even then the green colour of the water was apparent.

Although it's a completely different kind of luxury experience, I think the Emerald Lake Lodge should be on my hit list for my next trip out west.

The rest of the trip downhill to Golden will take about 50 minutes or so, depending on traffic, and it's an eye-popping experience -- but you'd best photograph it with a dashcam. There are some nearly level stretches, but there's no shortage of aggressive bends, and some of them throw in steep grades as well. A fair part of this spectacular road has been 4-laned, as part of a project to 4-lane the Trans-Canada Highway all the way from Kamloops to the Alberta border. But check out this internet photo of the notorious final stretch down into Golden, the most hair-raising part of all. It's two lanes only, steep, reduced speed limit (60 km/h, I think -- certainly that or less on some of the bends). As these internet aerial view shows, the road has had to be hacked out of the mountainside with explosives.

You can see a tiny railway bridge at the bottom of the canyon far below the road, and many parts of the CPR main line through the canyon had to be similarly created with endless rock blasting. This stretch of the line cost more lives to build per mile than any other part. In some areas the railway workers had to be dangled over the canyon walls in rope slings to drill holes and pack them with explosives. The railway builders referred to this canyon line as the Golden Stairs, and I wonder if this is how the town of Golden got its name.

Going down this hill, I took a chance while no one was near me going either up or down, slowed down, and took one picture out the windshield (I know, very unsafe!). This was to show the vast metal mesh nets which hang in front of the rock faces, to stop the many rogue chunks of falling rock from hurtling onto the roadway or the passing vehicles.

I can't imagine how they could possibly four-lane the existing roadway, and I fully expect them to use an alternative alignment -- but I also have no guess as to where that might go, unless it's through a very long tunnel. Stay tuned for further developments!

At Golden everyone encounters the Columbia River -- you, the Kicking Horse River, the CPR, and the TCH. And just like all the others, you turn northwest along the Columbia River's valley. This broad valley is actually called the Rocky Mountain Trench, and it stretches from southeast to northwest for hundreds of kilometres, separating the Rocky Mountains from the older (and geologically different) ranges to the west.

In order to reach Rogers Pass in the Selkirks, the CPR followed the Columbia northwards to the inflow of the Beaver River, and then backtracked southwards up the course of the Beaver River valley.

The irony of this long roundabout route from Golden to Rogers Pass is that the Pass is actually almost directly across the Rocky Mountain Trench from Golden -- west by a bit north.

The Trans-Canada follows a similar plan, although it shortens the trip a bit by climbing up and over the lower northern part of the Dogtooth range, which separates the two river valleys. Even with that help, it's nearly an hour's drive at steady highway speed before you climb up the western side of the Beaver valley, and then turn to the west and climb up into the steep-sided valley that is Rogers Pass.

You realize right away what an awe-inspiring, beautiful, and treacherous place this is. As the road climbs up the pass it has to go through a sequence of five heavy-duty concrete snowsheds under the steep slopes of the mountain called The Camels. This mountain must surely be the King of the Avalanches as far as highway travel on the Trans-Canada is concerned. Here's an early photo, taken shortly after the highway opened in 1962, showing two of the brand-new snowsheds.

Actually, just about every mountainside in Rogers Pass is equally dangerous. There are no less than 136 distinct avalanche paths in the pass. The Camels happens to be the one which most directly threatens the road.

If you're wondering where the railway line got to in this picture, the answer is literally right under your feet. By 1906, the CPR had lost far too many lives of workers to the numerous avalanches, and began boring the Connaught Tunnel under the pass. When it opened in 1910, the railway handed over the original right-of-way to Glacier National Park. In 1988, the even longer Mount Macdonald tunnel opened, and these two tunnels now gave the railway a double-tracked line bypassing the Rogers Pass area entirely. Parts of the old rail right-of-way are now used as walking trails -- I suspect that in this stretch, the narrowest part of the valley, that old right-of-way might be hidden under the pavement!

In the middle of the pass are two stopping places: a Parks Canada information and interpretation centre, and a monument to the builders of the highway through Rogers Pass on the summit.

Both areas give excellent views of the surrounding mountains. Northwards, you are looking at the complex of Mount Rogers -- a mountain on which each individual peak has its own distinguishing name. Rogers Peak is the one farthest to the left.

To the south, high up on the mountain,you can see the small remaining visible portion of the Illecillewaet Glacier.

In the early days of rail travel, the track passed in a broad curve around the southern side of the valley and right below the terminus of this ice sheet. A special hotel and station called Glacier House hosted each passenger train for an extended scenic stop. Today, the glacier has mostly retreated and the hotel is long gone too. But the ice still provides the essential kickstarter for the Illecillewaet River, whose turbulent course provides the route for highway and railway to follow downhill to the west.

The artillery gun displayed next to the monument isn't there are a war memorial. It's a memento of all the years which the Canadian Armed Forces has provided avalanche control services in the Pass, by firing artillery shells into high-mountain snow packs to release avalanches before the snow packs can grow to a dangerous size. This essential service continues to keep Rogers Pass open throughout the winter to the present day.

After visiting Rogers Pass, I backtracked to Golden, waiting out a lengthy (80-minute) traffic jam caused when a hydro wire fell across the highway in Golden itself. Finally I got there, and the power was still out in my hotel -- although it did come on 20 minutes later.

I had a lovely dinner on the patio of a restaurant which sits on a small island in the middle of the Kicking Horse River, very close to the confluence with the Columbia. It was a pleasant, low-key way to end a day filled with so much scenic drama.

No comments:

Post a Comment