May 1, 2023 was C-DAY!

On the final lap of this Round-the-World voyage for 2023, the Island Princess performed a full transit of the Panama Canal, using the original -- now called the "Historic" -- locks.

This marks my fourth, and finally successful, attempt to cruise through the Canal. I'd needed for various reasons to cancel three former cruise bookings. But really, I've been waiting for a chance to do this ever since I first read about the Canal, as a youngster. Call it 60 years of waiting time, give or take a few.

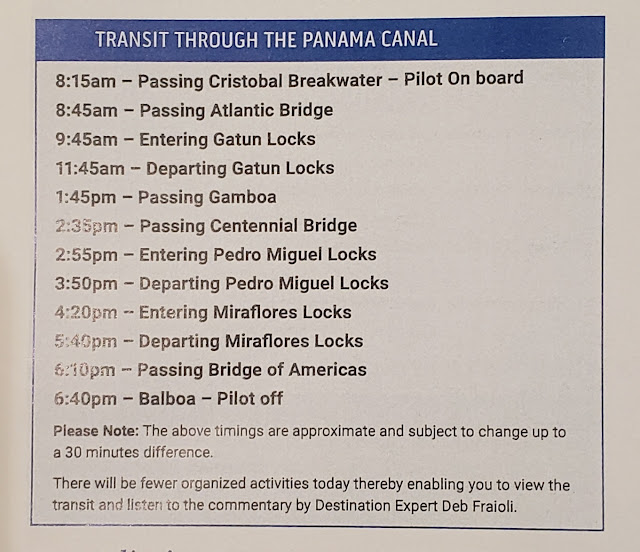

Instead of a normal photograph, I'm going to start off with a picture of the section from the daily Princess Patter newsletter, giving the approximate times (+/- 30 minutes) for the full Canal transit from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. This will help others planning Panama Canal full transit cruises to know roughly what to expect.

I stress the word "roughly" because the ship received a message during the night asking us to go an hour earlier, and there we were, slowly gliding in past the breakwater at 0705.

I'm tempted to say "from East to West," but as this map shows right away, that is a very misleading description, on one level at least. Due to the peculiar twist of the Isthmus of Panama, the most westerly part of the Panama Canal is actually the part closest to its "eastern" or Atlantic Ocean/Caribbean Sea entrance!

Canal Map and Schematic Attribution: Thomas Römer/OpenStreetMap data

Originally, it had been indicated that our transit of the Canal might begin as early as 6:00 am. I heaved a massive sigh of relief on seeing from the Patter that our actual start time would be +/- 8:15 am, a much more civilized hour! I heaved another massive sigh of relief on noticing that I had remembered to set my normal dinner time of 6:20 pm to an hour later at 7:20 pm for this one night! Phew!

Before we get started, one interesting technical note. Due to the limited dimensions and passing room in the Canal's channel in the Culebra Cut (labelled on the graphic by the former name of "Gaillard Cut"), between Gamboa and the Pedro Miguel Locks, it's necessary to operate that section of the waterway as a one-way-only facility whenever a ship of Panamax size like Island Princess (or larger) is making a full transit. The Canal authority gives ample advance notice whenever one-way operations in the Cut are scheduled.

And with that, here we go.

As we sailed in towards the breakwater, it was impossible to miss the multiple anchored ships. Social media are full of pics of ultra-gigantic cargo ships, but this view reminds us that a large part of the world's maritime commerce still travels in smaller vessels.

After picking up the pilot, our first eye-opener came as we sailed under the Atlantic Bridge, newest and highest of the three highway bridges which cross the Canal. It was opened in 2019.

Ahead of us we could see two lock systems. On the right were the historic Gatùn Locks, two parallel lines of three locks each, and that's where we were headed. On the left, we could see the new Agua Clara locks, a single line of three locks, but capable of handling much larger vessels.

The Panamax size limits leave precious little room for error on either side in the locks. At the narrowest points, there are only a handful of inches or centimetres to spare on either side of a Panamax ship like Island Princess, as shown in this view looking straight down from my stateroom balcony.

That's where the locomotives come into play. These electric-powered locomotives, known as "mules," use their wire-rope cables to connect them to ships transiting the locks. A team of eight mules is required to handle a Panamax-size ship, two at or near the bow on each side, and two at or near the stern on each side. Since my cabin was near the bow, my view was of the front two mules on the starboard side.

The Gatùn Locks are a single continuous flight of three steps, so the mules -- once connected -- controlled the Island Princess through the entire three-stage locking process.

The mules travel along a wide-gauge track on the edge of the lock, with a cogged rack rail in the middle. The use of the rack system not only lets the mules climb the steep stretch leading up from one lock to the next...

...but also gives maximum traction to ensure the cables remain taut and hold the ship exactly in position at all times. That's the mules' sole function: to keep a ship steady in the locks. They do not tow or pull the ship through the locks. Ships proceed on their own power. The mules prevent the ships from swerving or bumping into the lock walls.

Because the historic locks are paired, there will always be a second lock on one side or the other of your ship. The single chambers of the new locks create no such views as this one of a tanker going down the hill in the eastern lock as we went uphill in the western one.

We were nearing the upper water level in the final lock at Gatùn, so I took some time for a little breather on my balcony.

As your ship leaves the Gatùn Locks, look to the right. You'll see a concrete spillway, and a long curving earthen embankment stretching away to the forested hill across the valley. This is the Gatùn Dam, which blocked the Chagres River to create the large artificial lake on which you are now sailing. The completion of the dam, and the closure of the outlet valves, was the final step after all the rest of the canal was finished. As for all that earth it took to build the dam... well, we'll get to that soon enough.

Gatùn Lake is a weird place. The multiple islands, points, and little shoals are very reminiscent of the waters around the Thirty Thousand Islands in Georgian Bay, Ontario, but the tropical jungles and, even more, the steamy tropical heat, are all wrong for that comparison. It can seem very quiet and peaceful, and then all of a sudden you see another huge ship looming around the corner.

All were diverse sorts and conditions of cargo vessels except for one cruise ship, much smaller than the Island Princess.

Along the way, you reach a stretch where the Panama Canal Railway comes out of the jungle and runs close alongside the channel.

As you pass the midpoint of the transit, the port town of Gamboa looms into view. Served by both railway and highway, Gamboa is a major maintenance base for the Canal Authority, which must continually work at dredging channels and stabilizing hillsides to keep the Canal functioning all year round at peak efficiency.

Just past Gamboa, you pass the inflow of the Chagres River as it descends from the mountains of the Continental Divide, now looming ahead. Road and railway cross the Chagres on parallel bridges.

From this point until you arrive back at Pacific tidewater, every inch of the Canal had to be excavated, by combinations of explosives, steam shovels, trucks, rail cars, and good old-fashioned hand labour with picks and shovels. Now, look at the size of the excavation. This is the Culebra Cut.

And while you're looking at the size of that gap between the two sets of hills, remember that what you are seeing doesn't include the further 12 metres or more of excavated space now concealed by the water.

The highest of these mountains rises some 70 metres (230 feet) above the water's surface. The terraced face of the hill shows that the entire distance below that summit was formerly filled with earth and rock, every bit of which had to be removed and carted away.

Where did it all go? Some was used to fill up and level the sites where the locks were constructed. Some went into the long breakwaters which protect both entrances to the Canal. As for the rest, hasn't it been said that the best place to hide the evidence is right out in the open, in plain sight?

That's right. The Gatùn Dam.

This picture shows some hefty modern construction equipment, still engaged in reshaping the land to keep the Canal safer from erosion. Those vehicles give a more human scale to the size of all the machines and workers involved in the massive task of chewing their way through the Great Continental Divide -- for that is what this humpbacked ridge actually is.

Just past that highest peak of the mountains, you will sail under the Centennial Bridge. It was built to commemorate the hundredth anniversary of the Canal's opening, and it was crossed for the first time at the same time of the same day in 2013 as the first ship entered the Canal one hundred years earlier. On a more practical level, it carries the through traffic on the Pan-American Highway around the booming metropolis of Panama City, down on the west coast.

Shortly after we sailed under the Centennial Bridge, the channel widened out again and we faced another divide of the Canal -- on the left, the channel leading to the Pedro Miguel Locks, the first step down to the Pacific, and on the right, the channel leading to the 3-step flight of the Cocoli Locks in the new canal system.

Perfect sunny day, isn't it? While we were sitting there, waiting to enter the Pedro Miguel Lock, I went up to the top deck, turned around, and looked backwards to the Culebra Cut and Centennial Bridge, just a couple of kilometres behind us.

I thought for sure we were about to get drenched again, for the second day running, but that massive storm very considerately slid by and disappeared to the west on the north side of the Continental Divide. Massive sigh of relief. Interestingly, allthough we got none of the storm, the air afterwards became clearer, fresher, and less humid, with a drop in temperature, just as if that monster had slammed into us.

If you look at the Canal map, near the beginning of the post, you'll see at once that ships travelling in the old locks will get all the way down to sea level before the ships heading towards the Cocoli Locks have even entered the first lock. All of which helps to explain why the ship on the right is plainly farther uphill than our ship was when I took the picture.

At this point, we were just sailing out of the Pedro Miguel Lock and into the second and far smaller artificial lake in the Canal: Miraflores Lake.

At the far end, we entered the two-step Miraflores Locks, where I got these pictures. In the first picture, the red ship in front of us is now into the Pacific Ocean, while the white building up the hill to the right is alongside the upper entrance of the three Cocoli Locks.

Due to the opposite lock being empty, I got a grandstand view of one of the mules for that lock climbing the sharp hill between the lower and upper lock chambers.

And then, in our turn, we sailed out of the lower Miraflores Lock and were then back down to sea level. We passed through the busy harbour of Balboa.

There was one chance for a good look backwards at the new Cocoli Locks, with a ship coming down. All that "empty" space to the right of the lock actually consists of a series of large basins which retrieve and recycle something on the order of 80% of the water used in the locking process. The new Agua Clara locks at Gatùn are equipped with these recycling basins as well.

*************************

A few final helpful hints if you are going to transit the full canal for the first time:

[1] Do not miss the Culebra Cut and Centennial Bridge. That's the biggest scenic highlight of the whole transit of the Canal! I think a lot of passengers on my cruise missed it because it came in the early afternoon -- nap time!

[2] Don't fuss about which side your cabin is on for going through the canal. All locks in the system, whether old or new, can be used in both directions. Typically, a lock takes a ship down and then takes the next ship going up. It's pretty cool if you can look out your window and see another ship "right over there," but this is only possible if you are sailing through the historic locks, and even then you can never know before you get there. My room faced away from the second set of locks at Gatùn and Pedro Miguel but then faced an empty lock on the other side at Miraflores. There's no rule of "always on the right-side lock" or anything like that.

[3] Come prepared and dressed for fiendishly hot and humid weather. Temperatures in the 40-degree range of Celsius with 7 or 8 degrees of humidex on top of that are by no means impossible (we had 32C, feels like 38C and that was bad enough). Drink loads and loads of water. Know that the "cold" water tap on your ship will likely run warm and the temperature difference between hot tubs and swimming pools may be non-existent.

[4] Note that promenade decks and cabins on lower decks may be forbidden for outside access due to the locking procedures. This is one cruise where it pays to go higher in the ship.

[5] Schedules like the one shown above are engraved in Jello. We started off making most of the transit about 80-90 minutes ahead of the printed times, but ended up exiting the Canal under the Bridge of the Americas just 45 minutes ahead of the predicted schedule. Be alert for such changes.

No comments:

Post a Comment